See you in a tick!

- Aug 13, 2023

- 4 min read

It's my last week here at Big Oaks! It was a long and busy summer to be sure, but — at the risk of sounding cliche — it certainly felt like it went by very quickly!

As I mentioned in my last post, I spent the majority of this week out on the refuge with biologists from the Indiana Department of Health and the Department of Natural Resources, escorting them around the property and assisting them with their respective projects.

Early in the week I worked with the Department of Health to drag net some ticks accross our refuge's grasslands! To conduct a tick drag, a researcher uses a 1-square-metre (11 sq ft) strip of white cloth, usually corduroy, mounted on a pole that is tied to a length of rope. The researcher drags the cloth behind themselves through terrain that is suspected of harboring ticks, working in a grid-like pattern. They may also "flag" low-lying bushes and other vegetation by waving the cloth over them.

Drag-netting along the roadsides! Ticks clinging to the grass will detach themselves and hop onto the cloth as we drag it overhead, thinking it's a passing animal.

The researcher I was with was performing this collection in order to determine if there were any Asian Longhorned Ticks (ALHTs) in this part of the state. The longhorned tick, Haemaphysalis longicornis, is an invasive species of tick native to to eastern China, Japan, the Russian Far East, and Korea. They were first found in the United States in New Jersey in 2017, and since then, they have continued to spread slowly across the country, preying primarily on livestock.

Collecting tick larvae from the drag net. They're smaller than grass seeds, but after several blood meals and stages of growth, they'll become fully-fledged adults. We mostly collected lone star tick larvae during this run!

The main reason for the spread of ALHT is their unique trait of parthenogenesis, where the females can lay viable eggs without a male. Due to this natural form of asexual reproduction, these ticks can reproduce rapidly without needing to take the time to mate. Up to 3,000 eggs can be laid from one adult female ALHT. It is common to find hundreds of ticks on one animal.

Indiana is the 19th state to have a confirmed detection of an ALHT. These ticks feed on a wide range of animals including dogs, cats, horses, cattle, sheep, goats, and wildlife (including deer, several species of birds, raccoons, and opossums), as well as humans. They are more often found in tall grass and pasture areas and can adapt well to the environment, away from the host, and in a wide range of conditions.

While the invasion of this species is certainly a great concern, readers will be happy to know that we didn't detect any ALHTs here on the refuge! However routine surveys such as the one we performed here at Big Oaks this week will be necessary for understanding and preventing the spread of these ticks in the future.

After my work with the researcher from the department of health was done, I spent the latter part of the week collecting and examining spongy moth traps with another researcher from the Department of Natural Resources! Only a couple of months prior, another one of our interns went out with this biologist to hang the traps from trees around the refuge. We had about twenty of them in total, arranged in a grid several miles long.

Spongy moth trap arrangement and placement!

The spongy moth, Lymantria dispar, (formerly known as gypsy moth) is one of North America's most devastating invasive forest pests. The species originally evolved in Europe and Asia and was accidentally introduced near Boston, Massachusetts by an amateur entomologist in 1869. Since then, spongy moths have spread throughout the Northeast and into parts of the upper Midwest and Great Lakes states including Indiana.

The spongy moth is known to feed on the foliage of hundreds of species of trees and shrubs in North America but prefers oak trees. When spongy moth populations reach high levels, trees may be completely defoliated by feeding caterpillars. Several successive years of defoliation, along with contributions by other stress factors, often results in tree death. Spongy moth can be an expensive, messy problem for homeowners and, when out of control, can cause extensive damage to U.S. forests.

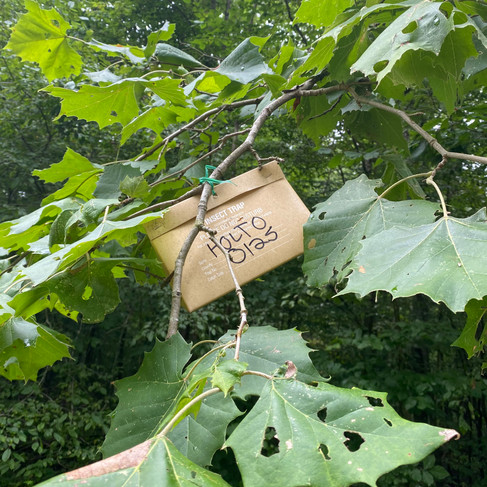

When traveling around the refuge with the DNR biologist, we visited each of the traps we placed earlier in the summer and examined their contents. The trap is made from paper folded into a triangular prism with openings on either side, and a sticky substance spread over every surface on the inside of the trap. Most of the traps we collected contained flies, bees, and other various small insects.

Removing a spongy moth trap stapled to the bark of an oak tree.

A good portion of the traps also contained some moths, but luckily we were able to determine that none of them were spongy moths. So once again, it looks like the refuge is safe from yet another invasive species!

Having mostly done the same types of surveys repeatedly over the course of the summer, it was a real treat to be able to try out invertebrate monitoring work during my last week of work here! Of course, repeating the same protocol over and over again under different conditions is necessary to assemble a meaningful set of data, but even so, sometimes the monotony of it can wear on you after a while.

That being said, I truly did cherish the summer I was able to spend here at Big Oaks NWR! I got to meet and learn from all sorts of people from different backgrounds, and work with species that I've never seen or heard of anywhere else! The work could definitely be rough or tedious at some points, but I'm coming away from this with some valuable experiences that I'll be able to carry on with me to my next position, and to other jobs throughout the rest of my career.

I hope you all enjoyed reading my posts this summer, and that you'll keep on following what's going on with the refuge and the other interns that come after us!

- Maeve

Comments